|

| Femme Maison Louise Bourgeois |

Safe as Houses

Bodies Under Siege in American Art

I did not yet know I was pregnant the day I saw Louise Bourgeois’s Femme Maison series at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where the panels sat in the middle of the drably titled exhibition “Louise Bourgeois: Paintings.” In fact, I’d walked to the museum straight from the office of a doctor who had reviewed my prior lab tests and ultrasounds and told me that I’d have an awfully hard time getting pregnant without a series of technological interventions. I recalibrated the units of my mental timeline: from months to years to, possibly, never. On the way out of the office I had peed in a cup one more time, just in case, a kind of reverse party favor.

“I don’t care if you’re having sex upside down, right side up, ten times a day,” he said. “Not gonna work.”

My first thought on the walk to the Met had been a resolution to switch practices, find someone who wouldn’t talk as though it were the most natural thing in the world to picture me in bed. My next, of course, was this Bartleby of a body, at first blush so serviceable, and then so quietly recalcitrant. It was an unseasonably hot day, the remaining cherry blossom petals smearing like oily sweat stains on the pavement. One by one, I imagined my way into the side effects of the medications that had been proposed to me, trying them on for size as I walked uptown. What if the prickle in my armpits and behind my knees were actually the start of a hot flash? Imagine it hotter yet. Then even hotter. What if the croissant I’m holding suddenly tasted like cardboard, or tasted so good I’d go to pieces if I couldn’t have another? What if my moods all quadrupled in size? Take this irritability I’m feeling now, perch it like a pillbox on my head. Then imagine it bigger. Bigger still.

The gargantuan floral arrangement in the entrance hall of the Met, bright scoreboard for the state of American horticulture (GMOs: up by a lot), puts a stop to most other thinking. And then there is the matter of finding the Bourgeois exhibition itself. No one who works at the museum seems to know where it is. I am directed to try the American Wing off the Temple of Dendur, then the exhibition space for the big headliner shows on the second floor, then, when I mention she is both French and American, to the vast plain of European art. Finally someone thinks she is on the ground floor of Modern and Contemporary Art, and I eventually reach the small warren of narrow, winding rooms in which her paintings have been situated.

Louise Bourgeois (1911–2010) is best known for brooding, minatory sculptures in which forms that suggest but do not quite replicate human organs loom, cluster, and spread. There have been periods of more straightforward representationalism—eyeballs, spiders—but her most powerful work conjures new and hybrid kinds of sensory organs and genitals, evolutionary byways or futures not yet our own. Potent lumps that could be both testicles and breasts at once, with a buzzing sense of factory production inside of them. Spiraling protuberances that are part tongue, part cochlea.

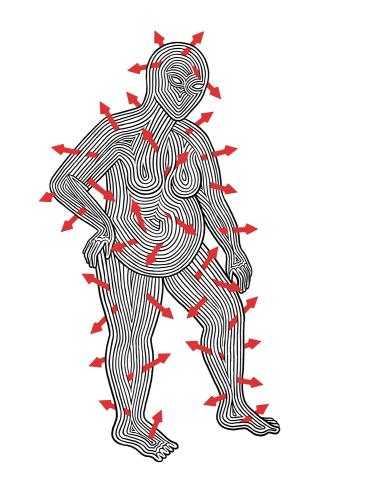

Her sculpture practice, which she began in the 1930s and first exhibited in the mid-1940s, exists in the future and the subjunctive: It is about forms that would or might be, or that require subjectivity, becoming real only in the context of assertion and belief. Her painting practice, which began in the 1930s and which she mostly gave up by the end of the ’40s in favor of sculpture, is to me a present-tense and past-tense affair. Here is the body. Here was the body, then. It is no wonder that her Femme Maison paintings—in which women’s nude bodies are stuffed into houses, or are turning into houses, or are being sliced and dismembered by the sharp carpentry of houses—became icons of radical feminism in the 1970s. They have the documentary force of the transcripts of consciousness-raising sessions, and while their lexicon is symbolic, it is as legible as a newspaper photograph.

In the Met exhibition there are four paintings called Femme Maison—woman-house, house-woman, or house-wife—all made between 1946 and 1947. In perhaps the least disturbing, a woman’s nude and armless torso is topped by a neoclassical façade in place of a head, the pillared building spouting tapered, striated clouds of steam or smoke that have the polished solidity of shallots or garlic bulbs. It’s a cousin to earlier paintings about concealment and revelation like René Magritte’s 1928 The Lovers (the famous kiss between hoods or shrouds) or even Picasso’s 1907 Les Demoiselles D’Avignon, in which at least two of the “faces” look more like wooden masks donned to hide whatever flesh might lie beneath. Bourgeois’s woman has become a house demurely on fire, but in a Halloween-ish way, the torso still unperturbed below. This is a kind of undressed dress-up.

The rest of the Femme Maison series gets progressively more lacerating. On one canvas, two headless female nudes try to communicate with each other, but one has a gigantic clapboard house shuttering her from the shoulders up, and the other has the whole top half of her body replaced by something between a dandelion seedhead and a puffball fungus, wearing its leaking seeds like punctuation marks but unable, clearly, to gin up much of a dialogue. Many-fingered smoke pours from the roof of the clapboard house, leaning toward dandelion-woman like a beckoning, but neither seems able to help the other. In another Femme Maison, the woman has now been turned into a house all the way down to her pelvis. All that’s left below are two kicking legs and two stony-looking pointed lumps where the woman’s labia would be, though in their flintiness they look less like a point of possible pleasure, more like the teats on the famous Capitoline Wolf statue that suckles a future full of empires and wars.

Bourgeois had left her home in France in 1938 after an accelerated romance with an American art historian, moving to New York City and experiencing a profound dislocation, intensified by the rapid transition within a few years from being a single, childless French artist to becoming an American wife and mother of three boys. The utter rupture, in which home becomes both a necessary anchor and a form of Capgras delusion, could have been psychologically shattering. In fact I’m sure it must have been. And yet she later said that the paintings, endowed as they are with New York’s “scientific, cruel, romantic quality,” could never have been painted in France. “Every one,” she said, “is American, from New York.” The loss of home, and then its ambivalent replacement with another both more solid and more squashing, becomes both a wound and a subject.

At the same time, the women in these paintings aren’t just having new dwellings foisted upon them: moving chronologically through Bourgeois’s work of the 1940s, the sense I get is of parts of the self being amputated and bionically replaced by house parts instead. Part of the old self is chopped, flattened, or squashed. I wonder if Bourgeois, as part of her assimilation to American life, saw The Wizard of Oz, which I’m sure she would have interpreted as both phantasmagoria and a truth too dark for most viewers to see it: the American farmhouse crushes the Wicked Witch of the East(ern Hemisphere), two glamorous but useless legs sticking out in ruby heels.

I needed the pugnacity of that Bourgeois exhibition to refract my own indignation at the age-old injustice that the things our bodies do or don’t do often have little relation to intention, desire, or merit. And that they will nonetheless be talked about, handled, and intervened upon as though they were properties to be appraised or improved. Bourgeois seemed to recognize on arrival that this was particularly true of American women—this new category of human that she was joining—and it seems that our contemporary political moment makes this truer every day. My own brief and minor dalliance with the idea of infertility, and now the petty indignities of pregnancy, hardly count in the litany of disaster and injustice wreaked upon the women in US counties that have zero abortion providers—already 89 percent before the fall of Roe—or the 58 percent of women who will soon live in a state hostile to most abortions now that Roe is overturned, and the roughly 750 women annually whose peripartum deaths make the US the most dangerous country in the developed world in which to give birth.

I am looking, these days, for art that tells the whole ungainly truth about how the body can be identified or misidentified with a home, a house, a shelter. It’s a comforting thought, that skin and bone are all we need as buttresses between self and world, that we have all the inner architecture we need to be haven to ourselves and others. But taken too far, it’s a butchery: that our softer selves might need to be crammed, lopped, or petrified in order to become the boxes and compartments that others need us to be.

I am glad, of course, that the Metropolitan Museum mounted the Bourgeois exhibition at all, though its ill-signed placement in a poky bottom corner of the building seemed like an unintended slight—then again, perhaps it was actually a witty nod to one of Bourgeois’s early and lasting subjects, the ways that our edifices mask deep channels of mixed and murky emotion and, perhaps, rage. Bourgeois’s house-women do not have visible basements, but still you sense the radon crackling through the charged air.

Gaston Bachelard’s unclassifiable book of philosophy and architecture, The Poetics of Space (1958), is one of those books that get passed, in increasingly ratty and spine-broken copies, from hand to hand among young poets. I like its attitude: that the aura of a house and the psychological power of a room’s configuration is something to take seriously, not because it’s a modern consumer’s responsibility to acquire and maintain the best and most updated product, but because dwellings really are like bodies, their caverns and symptoms ignored or degraded at our peril. Poets tend to like the book, I think, because one can think of poems, too, as buildings, with stanzas for rooms and lines for walls or windows. They resonate, they let air through or keep drafts out.

I do bristle, though, at the parts of the book that insist on identifying female bodies in particular with homes and buildings. He quotes approvingly from the poet Czesław Milosz’s references to house-as-mother, and to the writer Henri Bosco, who thinks of the house as both a mother and a protective female animal, “her odor penetrating maternally to my very heart.” Yes, yes, the womb, I know. But to be identified as hearth or cargo-hold when one spends so many decades not providing lodging to any prologue of human life!

My ambivalence to the identification—often gendered—between house and body is not, of course, my own invention, but rather one of the activating tensions, I think, in much of the art produced in the past century in America or by Americans. Shortly after my foray into Bourgeois’s work, I drove south to see a monumental exhibition of paintings by Joan Mitchell (1925–1992) at the Baltimore Museum of Art. Mitchell’s extra-large abstract expressionist canvases are magnificent explorations of color, rhythm, and velocity without a word of supporting commentary or biography, but are also the results of a radical experiment in uprooting and transplantation.

From 1949 to 1959, Mitchell was a young darling of the New York downtown art world, her movements followed by gossip columnists. Pretty in a severe and practical way, still built like a natural athlete (she had adored swimming and figure skating as a girl) despite the chosen constrictions of black turtleneck and clenched cigarette, she was one of the “sparkling Amazons” singled out by critics as that supposedly rare and surprising thing: a woman who could make excellent and groundbreaking art.

But then she left, for good, the glittering world in which she stood a good chance of remaining a crown jewel. By 1959, she had committed to living full-time in France, first in Paris and eventually settling outside the small village of Vétheuil, where she spent the rest of her life. Having moved there with a lover (artist Jean-Paul Riopelle, who lodged in the next village over but visited daily), she stayed on through the procession of relationships and uncouplings that drew partners out of, and then back to, the cities whence they came. Asked why she stayed on, she once told a journalist, “I’m too lazy to move,” but the remark seems deliberately obfuscating to me: The work, first taken up in her early career with a vast kaleidoscope of referents, from New York City bridges to the hemlock woods that populate a Wallace Stevens poem, begins to focus its intensity on the narrower lexicon of what can be seen from just one house, or what can be remembered by dreaming inside of it.

Despite her being generally classified as a “second-generation abstract expressionist,” Mitchell’s paintings are unafraid of metaphor and glancing figuration, of being caught thinking of particular existences outside of the canvas and its color values.

What’s most interesting to me about her work after arriving in Vétheuil is how every canvas gets its accelerant from whatever shapes, colors, or movements can simply be seen from the house or dreamed within its walls—a whole visual language that needs no novelty or gimmick apart from what the mind and the eye can do in one place.

Walking through the exhibition, the person accompanying me said he found Mitchell’s stasis terribly depressing, as though she hadn’t lived up to the promise of her initial talent by fastening herself so doggedly to the constraints of a limited site, a limited set of visual possibilities. It seems to me, though, that when an American male genius like Henry David Thoreau, or Robinson Jeffers, or Joseph Cornell commits to the radical experiment of holding still, of seeing all that one place can provide for the lone imagination, it is read as an intriguing and brilliant stroke of agency or self-knowledge. When it’s an American female genius like Joan Mitchell or Emily Dickinson, most of us still worry a bit for her, or pity the imagined resignation of her choice. This is the double bind of women’s bodies and houses: It is shocking when we register, à la Bourgeois, our discomfort at being stuffed into them or relegated to their confinements; it is sometimes equally dismaying when we stay inside them, commune deeply with them, and yet still claim the title of “artist.”

Mitchell’s Sunflower paintings of the 1960s and 1970s, inspired by the flowers visible from her studio (and of course by the legacy of van Gogh and others) are profusions of explosive movement, fertility, and centrifugal force. Made in one place, they are nevertheless hymns to voyage on a granular scale, to the raw chaos of particles and waves. Tiny strokes bead in piles or flee to the far edge of the canvas in pollinating clouds, while a heavy opulence of orangey-gold smolders at the focal point, dark empurpling shadows underscoring the electric buzz of bright activity at the top of the canvas. These are elations; their spiraling flocks of brushstroke form victory laps.

And then she revisited the image of sunflowers in 1990, two years before her death, making several diptychs and triptychs of oil on canvas on the same scale as the Sunflower paintings she had created in her earlier years at Vétheuil in the ’60s and ’70s. What’s most striking comparing the late vision to the earlier is the almost total absence of yellow in most versions: In my favorite diptych, the canvas is dominated by deep blue clusters of brushstrokes given an almost spherical density by highlights and lowlights of blood red and olive green.

If we lean into representational readings, these are sunflower heads with petals off and seeds out, the empty sockets that stand before being mowed under. Or, perhaps, the color-reversed picture—called a “negative afterimage” by neuroscientists—that one sees projected on one’s eyelids after staring too long at something: yellow flowers outside produce bruise-colored orbs in the mind’s eye. Either way, it’s a picture of epilogue, of the fleeting transformation of an image just before its final disappearance. Move away from metaphor and toward the painted surface itself, and the same holds true: a handful of near-vertical strokes prop up regions of color that tend toward downward concavity, and what tiny passages of pastel peep out get overlaid by encroaching darkness. Mitchell’s gestures by almost any account have little to do with self-pity, however: As the critic Donald Kuspit put it, reviewing these final works she completed before death, they “flatten the colors like pressed leaves in memory’s book, so they remain organized and structured to the end.”

Devising an organizing principle to structure one’s losses, to make grief itself into a staunch building material, is one of the miracles I thought about while taking in the work of Guadalupe Maravilla (1976–present), an American artist born in El Salvador whose work has been on view at the Brooklyn Museum this summer and fall and was visible at Virginia Commonwealth University’s Institute of Contemporary Art near the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Maravilla, who crossed the US border in the 1980s as an unaccompanied and undocumented eight-year-old fleeing the Salvadoran Civil War, and who later experienced intestinal cancer in young adulthood, makes a range of multimedia works that return to illness and migration as related forms of displacement, and which often use quasi-architectural sculptural forms to make alternative havens and homes where real life has stripped them bare or rendered them precarious. The most arresting and successful of these are his Disease Throwers, gorgeous and menacing mini-dwellings that radiate an almost sentient desire to protect their contents.

It’s hard to do justice in words to the Disease Throwers, but those that adhere to an overall room-like shape are each about the size of a toolshed or a ship’s cabin. There are also Disease Throwers that take the shape of gigantic thrones, with mixed materials on the floor outlining a larger border that shelters them. Most take the bleached colors of bones and natural fibers, while one startling example in the Brooklyn collection was a deeply pigmented, light-sucking black, smeared with the ash of the very same volcano thought to have displaced countless Mayan people from across Central America in the fifth century.

Maravilla describes the Disease Throwers as both works of art and aids to ritual and healing. Sitting silently for the most part in their galleries, they are flanked by video installations and sometimes live demonstrations showing how they could come to raucous life when their gongs, conch trumpets, and chimes are all activated, creating the kinds of vibratory therapies esteemed in Mayan and other cultures as a way of healing and purifying the sick body. (Ironically, several of the public performances of these sound-bath healing rituals have been canceled or postponed over the past couple years because of the pandemic.)

What I admire most in these works, however, is their unabashed pairing of bellicosity with hominess and shelter: a declaration that it is no contradiction to crave the safety and healing that these small havens can bring, and at the same time to send brazen salvoes of one’s presence out into the world; to lie on one’s back in these little lairs and also to make enough racket to scare off whatever forces would do one harm. Maravilla’s flatter works include reinventions of retablo paintings and of maps, charting his and his family’s near escapes from the perils of immigration, alienation, and illness.

These more straightforwardly allusive details are helpful codices to understand the currents running through the Disease Throwers, which are also hung with trinkets that feel like intimate shorthand for particular memories of the artist. Yet the habitation-like structures remain just underdetermined enough that each stranger encountering their charisma can, I think, borrow the shelter and the psychological armaments she needs to feel enclosed but awake, safe but gazing and sounding off.

In 1947, contemporaneously with her Femme Maison paintings, Louise Bourgeois made a small book of illustrations and accompanying text called He Disappeared Into Complete Silence. The drypoint and engravings show houses and fantastical architectural apparatuses, unpeopled but seemingly alert, in odd counterpoint to the glum tales printed beside them. My favorite text in the series is this one:

In the mountains of Central

France forty years ago, sugar

was

a rare product.

Children got one piece of

it at

Christmas time.

A little girl that I knew

when

She was my mother used to

be

Very fond and very jealous of

it.

She made a hole in the

ground

And hid her sugar in, and she

al-

Ways forgot that the earth is

damp.

Next to the story is a drawing of a towering, crystalline house with a fire raging on its central floor, not yet consuming the whole but heavy with the threat of it. It’s a tale that is partly a cruel joke about one’s mother, one that comes off only from the standpoint of American plenty and security—a tale about Back There, a tale made archaic in the space of a generation and one transatlantic migration. Back There, the girl who meant to safeguard the sugar was the agent of its dissolution. Driven by both desire and protectiveness, she is punished for both. And what does the house have to do with it? The engraved house, I think, is a temple of rage and restoration, where one finally, fleetingly, gets to have it both ways—the burning flame, yes, and also the intact walls.

Art is just that, I think: a space in which we encounter or fill in glimmers of simultaneous possibility, of paradox permitted, despite a surrounding world currently configured such that only one (or perhaps none) of the choices or beliefs we would entertain can be accommodated at one time.

I had just become pregnant, against all predictive data points, the day I had seen both Bourgeois’s work and the infertility specialist, and I now appear to have a bit of blank canvas ahead of me in which to work out my own provisional sketches of how I will welcome, accommodate, or repulse various associations between my body, houses, and homes. Yes, this body is a shelter for what I hope will become a new child. But long before that, it has been the house of my speech, thought, and writing, a fortress I am not willing to decommission from this charge. Should my life become more outwardly stilled, I want Mitchell’s voracious explosions, the maximal hunger for, and maximal expression of, what can be seen and done with dwelling. And should the need arise—with the creeping rollback in reproductive and sexual rights in the US, I fear it already has—may my body and all bodies find the magic structures that give them the right noise, the right spells, to fight besiegement.

Leave a comment